The film is less a documentary on the life of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hahn and more a guided meditation into mindfulness.

The last film I watched involving Benedict Cumberbatch was Avengers: Infinity War, where he plays that most mystical of Marvel characters, Dr Strange. This film, which Cumberbatch narrates in a voice so deep that the ocean would be jealous, could not be more different.

The film begins with a group of retreatants walking slowly in a French forest pausing, with a foot hovering in the air, before connecting again with the ground. The long tracking shot and sounds of nature are an invitation (echoed from the film’s title) for the audience to begin their own meditative journey into the life of the Plum Village Community established by Thich Nhat Han in 1982.

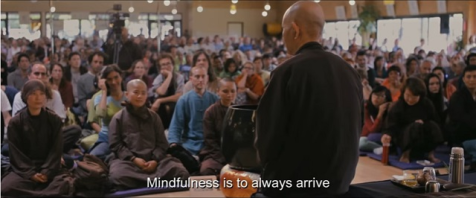

The first half of the film follows the Zen Buddhist teacher and his community through the seasons of the year. We observe a group of women being initiated into the order by having their hair ceremonially shaved to the point where blood is drawn. Two young Buddhists reflect on the boredom of doing the same thing everyday. Religious tourists flock in from all over the world by the coach load. But when a bell is rung everything stops, returning those in the film and the audience to the present.

Conversations at the reception desk stop mid-sentence, a string quartet playing in the grounds lift their bows mid-note. It serves as a timely reminder that in the midst of our busy lives we would do well to be more mindful of the here and now.

In the second act members of the community travel to the US. The juxtaposition of the peaceful and serene French countryside and the bustling streets of Manhattan leads to perhaps the funniest moment in the film. A monk leads a group in slow walking meditation along the sidewalks of New York while onlookers gawp in amazement that anyone would dare walk at such a pace in the city that never sleeps. The community then practice a sitting meditation in a park while being harangued by a Proselytising Christian, bible in hand, shouting that Buddha cannot save their souls from hell. There is a danger here of again portraying on screen only the extreme fringes of Christianity but this was rescued by another scene set in the States. A novice American Buddhist nun visits her aging and ailing father in a care home. The shock of seeing his daughter in robes for the first time brings him to tears. Helping him to control his breathing his daughter channels the spirit of her master’s ecumenism with the words ‘you don’t need to go anywhere to get to the Kingdom of Heaven. It is right here.’ It was beautiful and touching, human and transcendent.

What this film ultimately shows is that to practice mindfulness is hard. To sit in meditation for hours is hard. The film demands your concentration. But if you can dedicate yourself to it you will find, as the lights come up, a feeling of tranquility and peace, and maybe that’s the point the directors had in mind.